Hundreds of wilderness experts rushed to Ground Zero—and found a maddening, hellish new frontier.

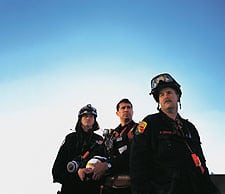

Left to right: physican Bill Trolan, caver Carl Levon Kustin, and wildland firefighter Bob Tooker after an exhausting shift Photo: James Rexroad

At the corner of Nassau and John Streets, five blocks from the New York Stock Exchange, the usual look is pinstripes or pearls, not tan canvas shirts, evergreen pants, and lug soles with aggressive treads. But there was Phil Musgrove, a Forest Service deputy logistics chief from Pendleton, Oregon, gazing up at the remaining towers of the lower Manhattan skyline.

“Never in my entire life,” Musgrove said, “did I think I’d be standing in New York City in a Forest Service uniform.”

Like a lot of people who earn their living protecting man from nature—wildfire experts, search-and-rescue specialists, cave “extraction” pros, and dog-team handlers—Musgrove, 49, was making his first visit to New York under the desperate circumstances following the terrorist attacks of September 11. The blond, 30-year firefighting veteran normally spends his time marshaling supplies, equipment, and crews to combat sprawling blazes out West. But two days after the World Trade Center towers collapsed, he found himself in a Sheraton hotel in New Jersey. There, along with 50 other Forest Service personnel, he was put to work orchestrating the flow of food, water, tools, and people into the massive search operation at Ground Zero. Now, on the seventh day after the attack, Musgrove stared at the silent and empty buildings of a war zone. “It’s unbelievable,” he said. “Unbelievable.”

A sense of disorientation and disbelief was quite normal among those who confronted this scene. From the very first minutes of the catastrophe through the slow denouement over the following weeks, many of the best-trained search-and-rescue workers from across the nation were thrown into a brutal maelstrom for which their experience was scant preparation. The scale of the catastrophe blurred the distinctions between what is urban and what is wild. Parts of New York became wilderness, not metaphorically, but literally. Stripped of power, water, and light, with its bridges, subways, and tunnels closed off, Manhattan in those first days held “frozen zones” as dark as any forest, as dry as any desert, and, with skies and avenues empty, as quiet as any outback. Only the natural acts of fires, earthquakes, and hurricanes could be used for feeble comparison. Time and again, the vocabulary of the outdoors was unleashed in jarring ways—like when a Colorado fireman compared the scene to an avalanche “because we’re not finding anybody alive under there.”

By early October, the Federal Emergency Management Agency had put 20 emergency response teams totalling 1,240 people on the case. That was in addition to the thousands of New York City fire department, police department, health department, and EMS personnel working the area daily; the cadres of New York State National Guard members, Forest Service workers, and FBI agents who joined FEMA in setting up a tent city and staging area in the Jacob Javitz Convention Center; and the thousands of volunteers and local emergency teams who answered the call. At its height, the number of workers and support staff surpassed 7,000.

In the face of the unimaginable, these people—among them wilderness firefighters from Texas and mountaineering doctors from California, K-9 cops from Kalamazoo and a crew of Zuni smoke jumpers from New Mexico, as well as amateur cave rescuers who drove by themselves from all across America—focused their skills on the vast heap of wires, cement, steel, and detritus so unfathomable they labeled it simply the Pile. They witnessed scenes that were impossible to describe, and though they made many selfless efforts, they gradually had to realize that search was not, in the end, going to lead to rescue.

***

The caver.

Those who came first were often the most affected, staggering away from the open wound in the city after exhausting themselves in a frenzy of digging. On day six, I met a man wobbling up the West Side Highway. He was glad to talk, though too spooked by his FEMA bosses to give his name. He had been sleeping in a rusting Land Cruiser parked nearby in the rubble; it was covered with caving stickers and an orange flag draped across the windshield that read emergency cave rescue. He’d aided the rescue efforts after the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 and the San Francisco earthquake in 1989, so he didn’t wait for an invitation. He raced up from Alabama in a straight shot, arriving on day three. He’d spent one long night crawling through the wreckage, hoping that his skills from a very different underworld would save someone’s life here at the mouth of hell. But he’d found nothing. “It’s indescribable,” he said. “There’s body parts everywhere. It’s much worse than Oklahoma City. The San Francisco quake was a joke compared to this.”

The caver tried, several times, to talk about the many shapes of death. His eyes were glazed. He waved his hands in front of his face. “It isn’t like anything,” he said. “It isn’t like anything.”

***

Shift work.

When the planes hit, Peter Welles was at a construction site in Secaucus, New Jersey, talking to his wife on the phone. A qualified rescue caver and wilderness EMT, Welles grabbed his ropes and vertical gear and rode an evacuation ferry into the disaster zone. By nightfall he was scouting for a K-9 team, clambering into confined spaces, and rappelling into a cracked-open manhole.

Following what turned out to be a false report, Welles led members of FDNY Engine Company 39 down the escalators as far as level five, searching for a woman trapped near a restaurant deep inside the PATH train concourse buried beneath the Pile. They stopped when they encountered a “gaping hole” that dropped 60 feet down to the tracks. He went back up for more rope and then showed a newly arrived FEMA team from Maine the way into the station, but as they were planning their descent, more debris in the area collapsed. “We all hightailed out of there,” he said.

Welles spent the rest of Wednesday and part of Thursday digging body parts out of the rubble and helped uncover the corpse of a fire chief. Eventually he took the ferry back across to Jersey, went home, and passed out. “I had a lot of training,” he told me later, “and it was very depressing that we didn’t help save anybody.”

After the first ad-hoc days, many who tried to volunteer were turned away. There were just too many people to manage effectively. FEMA moved in, its task forces of firefighters and civil engineers, communications and hazardous-materials specialists, doctors and heavy-equipment operators, rope riggers and rappelling experts working in 12-hour shifts. The task forces set up shop in the Javitz Center, which was filled with forklifts and laptops, smelled of wood pallets and bad spaghetti, and gleamed with reflective yellow backpacks, blood-red cargo containers, and neon green medical coolers. So many dog teams were called in (350 in all) that Charley Shimanski, an official at the Mountain Rescue Association who helped coordinate relief from Golden, Colorado, joked that “the representation of the wilderness community was probably greater in the four-legged variety than the two-legged variety.”

Still, wilderness people brought a wealth of survival intelligence. Dave Lesh, the assistant strike-team leader for Riverside-based California Task Force 6, a FEMA urban search-and-rescue crew, is a fire captain and an avid mountaineer. He compared the exhaustion of working the Pile and then sleeping only two hours a night to the 20-hour day he spent summiting Mount McKinley. “What applies is the stress, especially at altitude,” Lesh said. “The person who can deal with [mountaineering] can deal with an emergency.” Similarly, Carl Levon Kustin, the squad manager for Menlo Park-based California Task Force 3, told me that backpacking in the Sierra from the age of 15 had taught him the humility needed to confront the unimaginable. “You realize you are not in charge out there,” Kustin said. “In a way, I’m outside here. I’m outside in a very different, urban environment. But it draws on you to use every bit of experience and know-how, to look at this and use your imagination to deal with something you’ve never seen before.”

***

The Doctor.

After midnight on day eight, I found Dr. Bill Trolan in the base area of California Task Force 3. Trolan’s team had just finished an 18-hour shift. As a trickle of teammates came to him for sleeping pills, Trolan sat, slightly stunned, and puzzled at the way a love of sports, the outdoors, and medicine had combined to bring him here.

A mountaineer and skier with a wiry, powerful build, Trolan, 45, had helped organize the first Eco-Challenge races and had competed in the Raid Gauloises three times. In the field during adventure races, working with limited time and whatever was at hand, he’d learned to improvise. On the Pile, climbing harnesses were routine, with slippery steel, granulated concrete, and loose wires standing in for ice, mud, and shale. Trolan seemed to take comfort in the way the familiar rules of the wilderness applied. “Three points of contact at all times,” he told me. “Slow is fast, like in climbing. In the holes, it’s like caving. You have to look in four directions: above you, to the sides, and behind. You have to look back to learn your way out.”

Trolan lost a companion on Aconcagua once, a case of pulmonary edema, and he’s nearly lost his own life in the mountains. He called these “accepted risks” that prepared him for disaster work. I made the mistake of asking him what he saw in the holes. He started to answer, then fell into the same repetition I was hearing whenever the conversation turned to what could not be said.

“Put down your pen, put down your pen,” he said. I did, and he told me some of the things he’d had to do in the last day. “I thought I was prepared,” he said. Minutes later, telling an unrelated story, Trolan began crying quietly.

***

Crawling out.

It was 2 a.m., the start of day nine, when I left Trolan and walked home. California Task Force 3 was due back on the Pile in five hours. Down at the tip of Manhattan, you could see the ghastly white cloud, still churning up from the smoldering wreckage after more than a week, glowing from the arc lights of the night shift.

I thought of that first caver, one of many who had come and gone, doing what he could. As he was getting ready to leave, he’d said, “I’m going to drive out the highway until I get to some piece of rural America, and the first patch of green I see, I’m going to pitch my tent and sleep for days.” Then he walked back to his Land Cruiser, took down the orange emergency cave rescue flag, and went home.

Originally published in Outside, January 2002

via Unnatural Disaster | Outdoor Adventure | OutsideOnline.com.